(Full text of the famous speech delivered in 1869, at Dinajpur, West Bengal)

“O Ye, who are deeply merged in the knowledge of the love of God and also in deep thought about it, constantly drink, even after your emancipation, the most tasteful juice of the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, come on earth through Śrī Śukadeva Gosvāmi’s mouth carrying the liquid nectar out of the fallen and, as such, very ripe fruit of the Vedic tree which supplies all with their desired objects.” (Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, 1.1.3)

We love to read a book which we never read before. We are anxious to gather whatever information is contained in it and with such acquirement our curiosity stops. This mode of study prevails amongst a great number of readers, who are great men in their own estimation as well as in the estimation of those, who are of their own stamp. In fact, most readers are mere repositories of facts and statements made by other people. But this is not study. The student is to read the facts with a view to create, and not with the object of fruitless retention. Students like satellites should reflect whatever light they receive from authors and not imprison the facts and thoughts just as the Magistrates imprison the convicts in the jail! Thought is progressive. The author’s thought must have progress in the reader in the shape of correction or development. He is the best critic, who can show the further development of an old thought; but a mere denouncer is the enemy of progress and consequently of Nature. “Begin anew,” says the critic, because the old masonry does not answer at present. Let the old author be buried because his time is gone. These are shallow expressions. Progress certainly is the law of nature and there must be correction and developments with the progress of time. But progress means going further or rising higher. Now, if we are to follow our foolish critic, we are to go back to our former terminus and make a new race, and when we have run half the race, another critic of his stamp will cry out: “Begin anew, because the wrong road has been taken!” In this way our stupid critics will never allow us to go over the whole road and see what is in the other terminus. Thus the shallow critic and the fruitless reader are the two great enemies of progress. We must shun them.

The true critic, on the other hand, advises us to preserve what we have already obtained, and to adjust our race from that point where we have arrived in the heat of our progress. He will never advise us to go back to the point whence we started, as he fully knows that in that case there will be a fruitless loss of our valuable time and labor. He will direct the adjustment of the angle of the race at the point where we are. This is also the characteristic of the useful student. He will read an old author and will find out his exact position in the progress of thought. He will never propose to burn the book on the grounds that it contains thoughts which are useless. No thought is useless. Thoughts are means by which we attain out objects. The reader who denounces a bad thought does not know that a bad road is even capable of improvement and conversion into a good one. One thought is a road leading to another. Thus the reader will find that one thought which is the object to-day will be the means of a further object tomorrow. Thoughts will necessarily continue to be an endless series of means and objects in the progresses of humanity. The great reformers will always assert that they have come out not to destroy the old law, but to fulfil it. Vālmīki, Vyāsa, Plato, Jesus, Mohammed, Confucius and Caitanya Mahāprabhu assert the fact either expressly or by their conduct.

"The Bhāgavata like all religious works and philosophical performances and writings of great men has suffered from the imprudent conduct of useless readers and stupid critics."

The Bhāgavata like all religious works and philosophical performances and writings of great men has suffered from the imprudent conduct of useless readers and stupid critics. The former have done so much injury to the work that they have surpassed the latter in their evil consequence. Men of brilliant thought have passed by the work in quest of truth and philosophy, but the prejudice which they imbibed from its useless readers and their conduct, prevented them from making a candid investigation. Not to say of other people, the great genius of Raja Rammohun Roy, the founder of the sect of Brahmoism, did not think it worth his while to study this ornament of the religious library. He crossed the gate of the Vedānta, as set up by the māyāvāda construction of the designing Śaṅkarācarya, the chosen enemy of the Jains, and chalked his way out to the Unitarian form of the Christian faith, converted into an Indian appearance. Rammohun Roy was an able man. He could not be satisfied with the theory of illusion contained in the māyāvāda philosophy of Śaṅkara. His heart was full of love to Nature. He saw through the eye of his mind that he could not believe in his identity with God. He ran furious from the bounds of Śaṅkara to those of the Koran. There even he was not satisfied. He then studied the pre-eminently beautiful precepts and history of Jesus, first in the English translation and at last in the original Greek, and took shelter under the holy banners of the Jewish Reformer. But Rammohun Roy was also a patriot. He wanted to reform his country in the same way as he reformed himself. He knew it fully that truth does not belong exclusively to any individual man or to any nation of particular race. It belongs to God, and man whether in the poles or on the equator, has a right to claim it as the property of his Father. On these grounds he claimed the truths inculcated by the Western Saviour as also the property of himself and his countrymen, and thus he established the samaja of the Brahmos independently of what was in his own country in the beautiful Bhāgavata. His noble deeds will certainly procure him a high position in the history of reformers. But then, to speak the truth, he would have done more if he had commenced his work of reformation from the point where the last reformer in India left it. It is not our business to go further on this subject. Suffice it to say, that the Bhāgavata did not attract the genius of Rammohun Roy. His thought, mighty though it was, unfortunately branched like the Ranigunj line of the Railway, from the barren station of Śaṅkarācarya, and did not attempt to be an extension from the Delhi Terminus of the great Bhāgavata expounder of Nadia. We do not doubt that the progress of time will correct the error, and by a further extension the branch line will lose itself somewhere in the main line of progress. We expect these attempts in a abler reformer of the followers of Rammohun Roy.

The Bhāgavata has suffered alike from shallow critics both Indian and outlandish. That book has been accursed and denounced by a great number of our young countrymen, who have scarcely read its contents and pondered over the philosophy on which it is founded. It is owing mostly to their imbibing an unfounded prejudice against it when they were in school. The Bhāgavata, as a matter of course, has been held in derision by those teachers, who are generally of an inferior mind and intellect. This prejudice is not easily shaken when the student grows up unless he candidly studies the book and ruminates on the doctrines of Vaiṣṇavaism. We are ourselves witness of the fact. When we were in college, reading the philosophical works of the West and exchanging thoughts with the thinkers of the day, we had a real hatred towards the Bhāgavata. That great work looked like a repository of wicked and stupid ideas, scarcely adapted to the nineteenth century, and we hated to hear any arguments in its favour. With us then a volume of Channing, Parker, Emerson or Newman had more weight than the whole lots of Vaiṣṇava works. Greedily we poured over the various commentations of the Holy Bible and of the labors of the Tattwa Bodhini Sabhā, containing extracts from the Upaniṣads and the Vedānta, but no work of the Vaiṣṇavas had any favour with us. But when we advanced in age and our religious sentiment received development, we turned out in a manner Unitarian in our belief and prayed as Jesus prayed in the Garden. Accidentally, we fell in with a work about the Great Caitanya, and on reading it with some attention in order to settle the historical position of that Mighty Genius of Nadia, we had the opportunity of gathering His explanations of Bhāgavata, given to the wrangling Vedantist of the Benares School. The accidental study created in us a love for all the works which we find about our Eastern Savior. We gathered with difficulties the famous karcas in Sanskrit, written by the disciples of Caitanya. The explanations that we got of the Bhāgavata from these sources, were of such a charming character that we procured a copy of the Bhāgavata complete and studied its texts (difficult of course to those who are not trained up in philosophical thoughts) with the assistance of the famous commentaries of Śrīdhara Svāmi. From such study it is that we have at least gathered the real doctrines of the Vaiṣṇavas. Oh! What a trouble to get rid of prejudices gathered in unripe years!

As far as we can understand, no enemy of Vaiṣṇavaism will find any beauty in the Bhāgavata.The true critic is a generous judge, void of prejudices and party-spirit. One, who is at heart the follower of Mohammed will certainly find the doctrines of the New Testament to be a forgery by the fallen angel. A Trinitarian Christian, on the other hand, will denounce the precepts of Mohammed as those of an ambitious reformer. The reason simply is, that the critic should be of the same disposition of mind as that of the author, whose merit he is required to judge. Thoughts have different ways. One, who is trained up in the thoughts of the Unitarian Society or of the Vedānta of the Benares School, will scarcely find piety in the faith the Vaiṣṇavas. An ignorant Vaiṣṇava, on the other hand, whose business it is to beg from door to door in the name of Nityānanda will find no piety in the Christian. This is because, the Vaiṣṇava does not think in the way which the Christian thinks of his own religion. It may be, that both the Christian and the Vaiṣṇava will utter the same sentiment, but they will never stop their fight with each other only because they have arrived at their common conclusion by different ways of thoughts. Thus it is, that a great deal of ungenerousness enters into the arguments of the pious Christians when they pass their imperfect opinion on the religion of the Vaiṣṇavas.

"Party-spirit — that great enemy of truth — will always baffle the attempt of the inquirer, who tries to gather truth from religious works of their nations, and will make him believe that absolute truth is nowhere except in his old religious book."

Subjects of philosophy and theology are like the peaks of large towering and inaccessible mountains standing in the midst of our planet inviting attention and investigation. Thinkers and men of deep speculation take their observations through the instruments of reason and consciousness. But they take different points when they carry on their work. These points are positions chalked out by the circumstances of their social and philosophical life, different as they are in the different parts of the world. Plato looked at the peak of the Spiritual question from the West and Vyāsa made the observation from the East; so Confucius did it from further East, and Schlegel, Spinoza, Kant, Goethe from further West. These observations were made at different times and by different means, but the conclusion is all the same in as much as the object of observation was one and the same. They all hunted after the Great Spirit, the unconditioned Soul of the Universe. They could not but get an insight into it. Their words and expressions are different, but their import is the same. They tried to find out the absolute religion and their labours were crowned with success, for God gives all that He has to His children if they want to have it. It requires a candid, generous, pious and holy heart to feel the beauties of their conclusions. Party-spirit — that great enemy of truth — will always baffle the attempt of the inquirer, who tries to gather truth from religious works of their nations, and will make him believe that absolute truth is nowhere except in his old religious book. What better example could be adduced than the fact that the great philosopher of Benares will find no truth in the universal brotherhood of man and the common fatherhood of God? The philosopher, thinking in his own way of thought, can never see the beauty of the Christian faith. The way, in which Christ thought of his own father, was love absolute and so long as the philosopher will not adopt that way of thinking he will ever remain deprived of the absolute faith preached by the western Saviour. In a similar manner the Christian needs adopt the way of thought which the Vedantist pursued, before he can love the conclusions of the philosopher. The critic, therefore, should have a comprehensive, good, generous, candid, impartial and a sympathetic soul.

What sort of a thing is the Bhāgavata, asks the European gentlemen newly arrived in India. His companion tells him with a serene look, that the Bhāgavata is a book, which his Oriya bearer daily reads in the evening to a number of hearers. It contains a jargon of unintelligible and savage literature of those men who paint their noses with some sort of earth or sandal, and wear beads all over their bodies in order to procure salvation for themselves. Another of his companions, who has traveled a little in the interior, would immediately contradict him and say that the Bhāgavata is a Sanskrit work claimed by a sect of men, the Gosvāmis, who give mantras, like the Pope of Italy, to the common people of Bengal, and pardon their sins on payment of gold enough to defray their social expenses. A third gentlemen will repeat a third explanation. Young Bengal, chained up in English thoughts and ideas, and wholly ignorant of the Pre-Mohammed history of his own country, will add one more explanation by saying that the Bhāgavata is a book, containing an account of the life of Kṛṣṇa, who was an ambitious and an immoral man! This is all that he could gather from his grandmother while yet he did not go to school! Thus the Great Bhāgavata ever remains unknown to the foreigners like the elephant of the six blind who caught hold of the several parts of the body of the beast! But Truth is eternal and is never injured but for a while by ignorance.

The Bhāgavata itself tells us what it is:

nigama-kalpa-taror galitaṁ phalaṁ

śuka-mukhād amṛta-drava-saṁyutam

pibata bhāgavataṁ rasam ālayam

muhur aho rasikā bhuvi bhāvukāḥ

“It is the fruit of the tree of thought (Vedas) mixed with the nectar of the speech of Śukadeva. It is the temple of spiritual love! O! Men of Piety! Drink deep this nectar of Bhāgavata repeatedly till you are taken from this mortal frame.” (SB 1.1.3)

The Garuda-purāṇa says, again:

grantho’sta-dasa-sahasra-śrīmad-bhāgavatābhidha

sarva-vedetihāsānāṁ sāraṁ sāraṃ samuddhṛtam

sarva-vedānta-sāram hi śrī-bhāgavatam iṣyate

tad rasāmṛta-tṛptasya nānyatra syād rati-kvacit

“The Bhāgavata is composed of 18,000 ślokās. It contains the best parts of the Vedas and the Vedānta. Whoever has tasted it’s sweet nectar, will never like to read any other religious book.”

Every thoughtful reader will certainly repeat this eulogy. The Bhāgavata is preeminently the Book in India. Once enter into it, and you are transplanted, as it were, into the spiritual world where gross matter has no existence. The true follower of the Bhāgavata is a spiritual man who has already cut his temporary connection with phenomenal nature, and has made himself the inhabitant of that region where God eternally exists and loves. This mighty work is founded upon inspiration and its superstructure is upon reflection. To the common reader it has no charms and is full of difficulty. We are, therefore, obliged to study it deeply through the assistance of such great commentators as Śrīdhara Svāmi and the divine Caitanya and His contemporary followers.

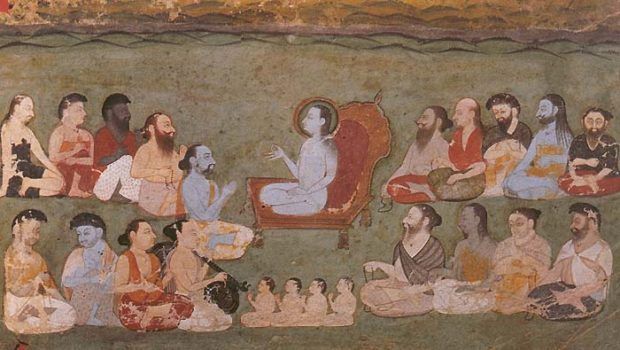

Now the great preacher of Nadia, who has been deified by His talented followers, tells us that the Bhāgavata is founded upon the four ślokās which Vyāsa received from Nārada, the most learned of the created beings. He tells us further that Brahma pierced through the whole universe of matter for years and years in quest of the final cause of the world but when he failed to find it abroad, he looked into the construction of his own spiritual nature, and there he heard the Universal Spirit speaking unto him, the following words:

śrī-bhagavān uvāca

jñānaṁ parama-guhyaṁ me yad vijñāna-samanvitam

sarahasyaṁ tad-aṅgaṁ ca gṛhāṇa gaditaṁ mayā

yāvān ahaṁ yathā-bhāvo yad-rūpa-guṇa-karmakaḥ

tathaiva tattva-vijñānam astu te mad-anugrahāt

aham evāsam evāgre nānyad yat sad-asat param

paścād ahaṁ yad etac ca yo ’vaśiṣyeta so ’smy aham

ṛte ’rthaṁ yat pratīyeta na pratīyeta cātmani

tad vidyād ātmano māyāṁ yathābhāso yathā tamaḥ

“Take, O Brahma! I am giving you the knowledge of my own self and of my relations and phases which is in itself difficult of access. You are a created being, so it is not easy for you to accept what I give you, but then I kindly give you the power to accept, so you are at liberty to understand my essence, my ideas, my form, my property and my action together with their various relations with imperfect knowledge. I was in the beginning before all spiritual and temporal things were created, and after they have been created I am in them all in the shape of their existence and truthfulness, and when they will be all gone I shall remain full as I was and as I am. Whatever appears to be true without being a real fact itself, and whatever is not perceived though it is true in itself are subjects of my illusory energy of creation, such as, light and darkness in the material world.” (SB. 2.9.31-34)

It is difficult to explain the above in a short compass. You must read the whole Bhāgavata for its explanation. When the great Vyāsa had effected the arrangements of the Vedas and the Upaniṣads, the completion of the eighteen Purāṇas with facts gathered from the recorded and unrecorded tradition of ages, and the composition of the Vedānta and the large Mahabharata, an epic poem of great celebrity, he began to ruminate over his own theories and precepts, and found like Faust of Goethe that he had up to that time gathered no real truth.

He fell back into his own self and searched his own spiritual nature and then it was that the above truth was communicated to him for his own good and the good of the world. The sage immediately perceived that his former works required supersession in as much as they did not contain the whole truth and nothing but the truth. In his new idea he got the development of his former idea of religion. He commenced the Bhāgavata in pursuance of this change. From this fact, our readers are expected to find out the position which the Bhāgavata enjoys in the library of Hindu theological works.

The whole of this incomparable work teaches us, according to our Great Caitanya, the three great truths which compose the absolute religion of man. Our Nadia preacher calls them saṁbandha, abhidheya and prayojana, i.e., the relation between the Creator and the created, the duty of man to God and the prospects of humanity. In these three words is summed up the whole ocean of human knowledge as far as it has been explored up to this era of human progress. These are the cardinal points of religion and the whole Bhāgavata is, as we are taught by Caitanya, an explanation both by precepts and example, of these three great points.

In all its twelve skandhas or divisions the Bhāgavata teaches us that there is only one God without a second, Who was full in Himself and is and will remain the same. Time and space, which prescribe conditions to created objects are much below His Supreme Spiritual nature, which is unconditioned and absolute. Created objects are subject to the influence of time and space, which form the chief ingredients of that principle in creation which passes by the name of māyā. māyā is a thing which is not easily understood by us who are subject to it, but God explains, as much as we can understand in our present constitution, this principle through our spiritual perception. The hasty critic starts like an unbroken horse at the name of māyā and denounces it as a theory identical with that of Bishop Berkeley. “Be patient in your inquiry,” is our immediate reply. In the mind of God there were ideas of all that we perceive in eternal existence with him, or else God loses the epithet of omniscient so learnedly applied to Him. The imperfect part of nature implying want proceeded also from certain of those ideas, and what, but a principle of māyā, eternally existing in God subject to His Omnipotence, could have a hand in the creation of the world as it is? This is styled as the māyā-śakti of the omnipresent God. Cavil as much as you can. This is a truth in relation to the created universe.

"The scandal of the ideal theory consists in its tendency to falsify nature, but the theory as explained in the Bhāgavata makes nature true, if not eternally true as God and His ideas."

This māyā intervenes between us and God as long as we are not spiritual, and when we are able to break off her bonds, we, even in this mortal frame, learn to commune in our spiritual nature with the unconditioned and the absolute. No, māyā does not mean a false thing only, but it means concealment of eternal truth as well. The creation is not māyā itself but is subject to that principle. Certainly, the theory is idealistic but it has been degraded into foolishness by wrong explanations. The materialist laughs at the ideal theory saying, how could his body, water, air and earth be mere ideas without entity, and he laughs rightly when he takes Śaṅkarācarya’s book in his hand at the butt end of his ridicule. The true idealist must be a dualist also. He must believe all that he perceives as nature created by God full of spiritual essence and relations, but he must not believe that the outward appearance is the truth. The Bhāgavata teaches that all that we healthily perceive is true, but its material appearance is transient and illusory. The scandal of the ideal theory consists in its tendency to falsify nature, but the theory as explained in the Bhāgavata makes nature true, if not eternally true as God and His ideas. What harm there can be if man believes in nature as spiritually true and that the physical relations and phases of society are purely spiritual?

"The Bhāgavata teaches us this relation between man and God, and we must all attain this knowledge."

No, it is not merely changing a name but it is a change in nature also. Nature is eternally spiritual but the intervention of māyā makes her gross and material. Man, in his progress attempts to shake off this gross idea, childish and foolish in its nature and by subduing the intervening principle of māyā, lives in continual union with God in his spiritual nature. The shaking off this bond is salvation of the human nature. The man who has got salvation will freely tell his brother that “If you want to see God, see me, and if you want to be one with God, you must follow me.” The Bhāgavata teaches us this relation between man and God, and we must all attain this knowledge. This sublime truth is the point where the materialist and the idealist must meet like brothers of the same school and this is the point to which all philosophy tends.

This is called saṁbandha-jñāna of the Bhāgavata, or, in other words, the knowledge of relations between the conditioned and the Absolute. We must now attempt to explain the second great principle inculcated by the Bhāgavata, i.e., the principle of duty. Man must spiritually worship his God. There are three ways, in which the Creator is worshipped by the created.

vadanti tat tattva-vidas tattvaṁ yaj jñānam advyayam

brahmeti paramātmeti bhagavān iti śabdyate

All theologists agree in maintaining that there is only one God without a second, but they disagree in giving a name to that God owing to the different modes of worship, which they adopt according to the constitution of their mind. Some call Him by the name of brahman, same by the name of paramātma and others by the name of bhagavan. Those who worship God as infinitely great in the principle of admiration call him by the name of brahman. This mode is called jñāna or knowledge. Those who worship God as the Universal Soul in the principle of spiritual union with him give him the name of paramātma. This is yoga. Those who worship God as all in all with all their heart, body and strength style Him as bhagavān. This last principle is bhakti. The book that prescribes the relation and worship of bhagavān, procures for itself the name of Bhāgavata and the worshipper is also called by the same name.

Such is Bhāgavata which is decidedly the Book for all classes of theists. If we worship God spiritually as all in all with our heart, mind, body and strength, we are all Bhāgavatas and we lead a life of spiritualism, which neither the worshipper of brahman, nor the yogi uniting his soul with(paramātma) the universal soul can obtain. The superiority of the Bhāgavata consists in the uniting of all sorts of theistic worship into one excellent principle in human nature, which passes by the name of bhakti. This word has no equivalent in the English language. Piety, devotion, resignation and spiritual love unalloyed with any sort of petition except in the way of repentance, compose the highest principle of bhakti. The Bhāgavata tells us to worship God in that great and invaluable principle, which is infinitely superior to human knowledge and the principle of yoga.

Our short compass will not admit of an explanation of the principle of bhakti beautifully rising from its first stage of application in the form of Brahmic worship in the shape of admiration which is styled the śānta-rasa, to the fifth or the highest stage of absolute union in love with God, sweetly styled the madhura-rasa of prema-bhakti. A full explanation will take a big volume which is not our object here to compose. Suffice it to say that the principle of bhakti passes five distinct stages in the course of its development into its highest and purest form. Then again when it reaches the last form, it is susceptible of further progress from the stage of prema (love) to that of mahābhāva which is in fact a complete transition into the spiritual universe where God alone is the bride-groom of our soul.

"Material examples are absolutely necessary for the explanation of spiritual ideas. The Bhāgavata believes that the spirit of nature is the truth in nature and is the only practical part of it."

The voluminous Bhāgavata is nothing more than a full illustration of this principle of continual development and progress of the soul from gross matter to the all-perfect Universal Spirit who is distinguished as personal, eternal, absolutely free, all powerful and all intelligent. There is nothing gross or material in it. The whole affair is spiritual. In order to impress this spiritual picture upon the student who attempts to learn it, comparisons have been made with the material world, which cannot but convince the ignorant and the impractical. Material examples are absolutely necessary for the explanation of spiritual ideas. The Bhāgavata believes that the spirit of nature is the truth in nature and is the only practical part of it.

The phenomenal appearance of nature is truly theoretical, although it has had the greatest claim upon our belief from the days of our infancy. The outward appearance of nature is nothing more than a sure index of its spiritual face. Comparisons are therefore necessary. Nature as it is before our eyes, must explain the spirit, or else the truth will ever remain concealed, and man will never rise from his boyhood though his whiskers and beard grow white as the snows of the Himalayas. The whole intellectual and moral philosophy is explained by matter itself. Emerson beautifully shows how all the words in moral philosophy originally came from the names of material objects. The words heart, head, spirit, thought, courage, bravery, were originally the common names of some corresponding objects in the material world. All spiritual ideas are similarly pictures from the material world, because matter is the dictionary of spirit, and material pictures are but the shadows of the spiritual affairs which our material eye carries back to our spiritual perception. God in his infinite goodness and kindness has established this unfailing connection between the truth and the shadow in order to impress upon us the eternal truth which he has reserved for us. The clock explains the time, the alphabet points to the gathered store of knowledge, the beautiful song of a harmonium gives the idea of eternal harmony in the spirit world, today and tomorrow and day-after-tomorrow thrust into us the ungrasped idea of eternity and similarly material pictures impress upon our spiritual nature the truly spiritual idea of religion. It is on these reasonable grounds that Vyāsa adopted the mode of explaining our spiritual worship with some sorts of material phenomena, which correspond with the spiritual truth. Our object is not to go into details, so we are unable to quote some of the illustrations within this short compass.

We have also the practical part of the question in the 11th book of Bhāgavata. All the modes by which a man can train himself up to prema- bhakti as explained above, have been described at great length. We have been advised first of all, to convert ourselves into most grateful servants of God as regards our relation to our fellow brethren. Our nature has been described as bearing three different phases in all our bearings of the world. Those phases are named sattva, rajas, tamas. Sattva-guṇa is that property in our nature, which is purely good as far as it can be pure in our present state. Rajo-guṇa is neither good nor bad. Tamo-guṇa is evil. Our pravṛttīs or tendencies and affections are described as the mainspring of all our actions, and it is our object to train up those affections and tendencies to the standard of sattva-guna, as decided by the moral principle. This is not easily done. All the springs or our actions should be carefully protected from tamo-guṇa, the evil principle, by adopting the rajo- guna at first, and when that is effected, man should subdue his rajo-guṇa by means of the natural sattva- guna which is the most powerful of them cultivated. Lust, idleness, wicked deeds and degradation of human nature by intoxicating principles are described as exclusively belonging to tamo-guṇa, the evil phase of nature. These are to be checked by marriage, useful work and abstinence from intoxication and trouble to our neighbours and inferior animals. Thus when rajo- guna has obtained supremacy in the heart, it is our duty to convert that rajo-guṇa into sattva-guna which is pre-eminently good. That married love, which is first cultivated, must now be sublimated into holy, good and spiritual love, i.e., love between soul and soul. Useful work will now be converted into work of love and not of disgust or obligation. Abstinence from wicked work will be made to lose its negative appearance and converted into positive good work. Then we are to look to all living beings in the same light in which we look to ourselves, i.e., we must convert our selfishness into all possible disinterested activity towards all around us. Love, charity, good deeds and devotion to God will be our only aim. We then become the servants of God by obeying his High and Holy wishes. Here we begin to be bhaktas and we are susceptible of further improvement in our spiritual nature, as we have described above. All this is covered by the term abhidheya, the second cardinal point in the supreme religious work, the Bhāgavata . We have now before us, the first two cardinal points in our religion, explained somehow or other in the terms and thoughts expressed by our saviour who lived only four and a half centuries ago in the beautiful town of Nadia, situated on the banks of the Bhagirathi. We must now proceed to the last cardinal point termed by the great Re-establishes prayojana or prospects.

What is the object of our spiritual development, our prayer, our devotion and our union with God? The Bhāgavata tells that the object is not enjoyment or sorrow, but continual progress in spiritual holiness and harmony.

In the common-place books of the Hindu religion in which the rajo and tamo-guṇa have been described as the ways of religion, we have descriptions of a local heaven and a local hell; the Heaven as beautiful as anything on earth and the Hell as ghastly as any picture of evil. Besides this Heaven we have many more places, where good souls are sent up in the way of promotion! There are 84 divisions of the hell itself, some more dreadful than the one which Milton has described in his “Paradise Lost” . These are certainly poetical and were originally created by the rulers of the country in order to check evil deeds of the ignorant people, who are not able to understand the conclusions of philosophy. The religion of the Bhāgavata is free from such a poetry. Indeed, in some of the chapters we meet with descriptions of these hells and heavens, and accounts of curious tales, but we have been warned somewhere in the book, not to accept them as real facts, but as inventions to overawe the wicked and to improve the simple and the ignorant. The Bhāgavata, certainly tells us a state of reward and punishment in future according to deeds in our present situation.

"If the whole stock of Hindu theological works which preceded the Bhāgavata were burnt like the Alexandrian library and the sacred Bhāgavata preserved as it is, not a part of the philosophy of the Hindus except that of the atheistic sects, would be lost."

All poetic inventions, besides this spiritual fact, have been described as statements borrowed from other works in the way of preservation of old traditions in the book which superseded them and put an end to the necessity of their storage. If the whole stock of Hindu theological works which preceded the Bhāgavata were burnt like the Alexandrian library and the sacred Bhāgavata preserved as it is, not a part of the philosophy of the Hindus except that of the atheistic sects, would be lost. The Bhāgavata therefore, may be styled both as a religious work and a compendium of all Hindu history and philosophy.

The Bhāgavata does not allow its followers to ask anything from God except eternal love towards Him. The kingdom of the world, the beauties of the local heavens and the sovereignty over the material world are never the subjects of Vaiṣṇava prayer. The Vaiṣṇava meekly and humbly says, “Father, Master, God, Friend and Husband of my soul! Hallowed be Thy name! I do not approach You for anything which You have already given me. I have sinned against You and I now repent and solicit Your pardon. Let Thy holiness touch my soul and make me free from grossness. Let my spirit be devoted meekly to Your Holy service in absolute love towards Thee. I have called You my God, and let my soul be wrapped up in admiration at Your greatness! I have addressed You as my Master and let my soul be strongly devoted to your service. I have called You my friend, and let my soul be in reverential love towards You and not in dread or fear! I have called you my husband and let my spiritual nature be in eternal union with You, for ever loving and never dreading, or feeling disgust. Father! let me have strength enough to go up to You as the consort of my soul, so that we may be one in eternal love! Peace to the world.”!

Of such a nature is the prayer of the Bhāgavata. One who can read the book will find the highest form of prayer in the expressions of Prāhlāda towards the universal and omnipresent Soul with powers to convert all unholy strength into meek submission or entire annihilation. This prayer will show what is the end and object of Vaiṣṇavas life. He does not expect to be the king of a certain part of the universe after his death, nor does he dread a local fiery and turbulent hell, the idea of which would make the hairs of young Hamlet stand erect like the forks of a porcupine! His idea of salvation is not total annihilation of personal existence as the Buddhists and the twenty-four gods of the Jains procured for themselves! The Vaiṣṇava the meekest of all creatures devoid of all ambition. He wants to serve God spiritually after death as he has served Him both in spirit and matter while here. His constitution is a spirit and his highest object of life is divine and holy love.

There may be a philosophical doubt. How the human soul could have a distinct existence from the universal Soul when the gross part of the human constitution will be, no more? The Vaiṣṇava can’t answer it, nor can any man on earth explain it. The Vaiṣṇava meekly answers, he feels the truth but he cannot understand it. The Bhāgavata merely affirms that the Vaiṣṇava soul when freed from the gross matter will distinctly exist not in time and space but spiritually in the eternal spiritual kingdom of God where love is life, and hope and charity and continual ecstasy without change are its various manifestations.

In considering about the essence of the Deity, two great errors stare before us and frighten us back to ignorance and its satisfaction. One of them is the idea that God is above all attributes both material and spiritual and is consequently above all conception. This is a noble idea but useless. If God is above conception and without any sympathy with the world, how is then this creation? This Universe compose of properties? the distinctions and phases of existence? the differences of value? Man, woman, beast, trees, magnetism, animal magnetism, electricity, landscape, water and fire. In that case Śaṅkarācārya’s māyāvāda theory would be absolute philosophy.

"Our ideas are constrained by the idea of space and time, but God is above that constraint. This is a glimpse of Truth and we must regard it as Truth itself: often, says Emerson, a glimpse of truth is better than an arranged system and he is right."

The other error is that God is all attribute, i.e. intelligence, truth, goodness and power. This is also a ludicrous idea. Scattered properties can never constitute a Being. It is more impossible in the case of belligerent principles, such as justice and mercy and fulness and creative power. Both ideas are imperfect. The truth, as stated in the Bhāgavata is that properties, though many of them belligerent, are united in a spiritual Being where they have full sympathy and harmony. Certainly this is beyond our comprehension. It is so owing to our nature being finite and God being infinite. Our ideas are constrained by the idea of space and time, but God is above that constraint. This is a glimpse of Truth and we must regard it as Truth itself: often, says Emerson, a glimpse of truth is better than an arranged system and he is right.

The Bhāgavata has, therefore, a personal, all-intelligent, active, absolutely free, holy, good, all-powerful, omnipresent, just and merciful and supremely spiritual deity without a second, creating, preserving all that is in the universe. The highest object of the Vaiṣṇava is to serve that Infinite Being for ever spiritually in the activity of Absolute Love.

These are the main principles of the religion inculcated by the work, called the Bhāgavata, and Vyāsa, in his great wisdom, tried his best to explain all these principles with the aid of pictures in the material world. The shallow critic summarily rejects this great philosopher as a man-worshipper. He would go so far as to scandalise him as a teacher of material love and lust and the injurious principles of exclusive asceticism. The critic should first read deeply the pages of the Bhāgavata and train his mind up to the best eclectic philosophy which the world has ever obtained, and then we are sure he will pour panegyrics upon the principal of the College of Theology at Badrikāśrama which existed about 4,000 years ago. The shallow critic’s mind will undoubtedly be changed, if he but reflects upon one great point, i.e., how is it possible that a spiritualist of the school of Vyāsa teaching the best principles of theism in the whole of the Bhāgavata and making the four texts quoted in the beginning as the foundation of his mighty work, could have forced upon the belief of men that the sensual connection between men with certain females is the highest object of worship! This is impossible, dear critic! Vyāsa could not have taught the common vairagi to set up an akhāḍā (a place worship) with a number of females! Vyāsa, who could teach us repeatedly in the whole of Bhāgavata that sensual pleasures are momentary like the pleasures of rubbing the itching hand and that man’s highest duty is to have spiritual love with God, could never have prescribed the worship of sensual pleasures. His descriptions are spiritual and you must not connect matter with it. With this advice, dear critic, go through the Bhāgavata and I doubt not you will, in three months, weep and repent to God for despising this revelation through the heart and brain of the great Bādarāyaṇa.

Yes, you nobly tell us that such philosophical comparisons produced injury in the ignorant and the thoughtless. You nobly point to the immoral deeds of the common vairagis, who call themselves “The followers of the Bhāgavata and the great Caitanya”. You nobly tell us that Vyāsa, unless purely explained, may lead thousands of men into great trouble in time to come. But dear critic! Study the history of ages and countries! Where have you found the philosopher and the reformer fully understood by the people? The popular religion is fear of God and not the pure spiritual love which Plato, Vyāsa, Jesus, and Caitanya taught to their respective peoples! Whether you give the absolute religion in figures or simple expressions, or teach them by means of books or oral speeches, the ignorant and the thoughtless must degrade it. It is indeed very easy to tell and swift to hear that absolute truth has such an affinity with the human soul that it comes through it as if intuitively. No exertion is necessary to teach the precepts of true religion. This is a deceptive idea. It may be true of ethics and of the alphabet of religion but not of the highest form of faith which requires an exalted soul to understand. It certainly requires previous training of the soul in the elements of religion just as the student of the fractions must have a previous attainment in the elemental numbers and figures in arithmetic and geometry. Truth is good, is an elemental truth, which is easily grasped by the common people. But if you tell a common patient, that God is infinitely intelligent and powerful in His spiritual nature, He will conceive a different idea from what you entertain of the expression. All higher truths, though intuitive, require previous education in the simpler ones. That religion is the purest, which gives you the purest idea of God, and the absolute religion requires an absolute conception by man of his own spiritual nature. How then is it possible that the ignorant will ever obtain the absolute religion as long as they are ignorant? When thought awakens, the thinker is no more ignorant and is capable of obtaining an absolute idea of religion. This is a truth and God has made it such in His infinite goodness, impartiality and mercy. Labor has its wages and the idle must never be rewarded. Higher is the work, greater is the reward is a useful truth. The thoughtless must be satisfied with superstition till he wakes and opens his eyes to the God of love. The reformers, out of their universal love and anxiety for good endeavour by some means or other to make the thoughtless drink the cup of salvation, but the latter drink it with wine and fall into the ground under the influence of intoxication for the imagination has also the power of making a thing what it never was. Thus it is that the evils of nunneries and the corruptions of the akhada proceeded. No, we are not to scandalise the Saviour of Jerusalem or the Saviour of Nadia for these subsequent evils. Luthers, instead of critics, are what we want for the correction of those evils by the true interpretation of the original precepts.

Two more principles characterise the Bhāgavata, viz., liberty and progress of the soul throughout eternity. The Bhāgavata teaches us that God gives us truth and He gave it to Vyāsa, when we earnestly seek for it. Truth is eternal and unexhausted. The soul receives a revelation when it is anxious for it. The souls of the great thinkers of the by-gone ages, who now live spiritually, often approach our inquiring spirit and assist it in its development. Thus Vyāsa was assisted by Nārada and Brahma. Our śāstras, or in other words, books of thought do not contain all that we could get from the infinite Father. No book is without its errors. God’s revelation is absolute truth, but it is scarcely received and preserved in its natural purity. We have been advised in the 14th Chapter of 11th skandha of the Bhāgavata to believe that truth when revealed is absolute, but it gets the tincture of the nature of the receiver in course of time and is converted into error by continual exchange of hands from age to age. New revelations, therefore, are continually necessary in order to keep truth in its original purity. We are thus warned to be careful in our studies of old authors, however wise they are reputed to be. Here we have full liberty to reject the wrong idea, which is not sanctioned by the peace of conscience. Vyāsa was not satisfied with what he collected in the Vedas, arranged in the Puranas and composed in the Mahabharata. The peace of his conscience did not sanction his labours. It told him from inside “ No, Vyāsa! you can’t rest contented with the erroneous picture of truth which was necessarily presented to you by the sages of by-gone days! You must yourself knock at the door of the inexhaustible store of truth from which the former ages drew their wealth. Go, go up to the Fountain¬ head of truth where no pilgrim meets with disappointment of any kind. Vyāsa did it and obtained what he wanted. We have been all advised to do so. Liberty then is the principle, which we must consider as the most valuable gift of God. We must not allow ourselves to be led by those who lived and thought before us. We must think for ourselves and try to get further truths which are still undiscovered. In the 23rd text 21st Chapter 11th skandha of the Bhāgavata we have been advised to take the spirit of the śāstras and not the words. The Bhāgavata is therefore a religion of liberty, unmixed truth and absolute love.

The other characteristic is progress. Liberty certainly is the father of all progress. Holy liberty is the cause of progress upwards and upwards in eternity and endless activity of love. Liberty abused causes degradation and the Vaiṣṇava must always carefully use this high and beautiful gift of God. The progress of the Bhāgavata described as the rise of the soul from Nature up to Nature’s God, from māyā, the absolute and the infinite. Hence the Bhāgavata says of itself:

nigama-kalpa-taror galitaṁ phalaṁ

śuka-mukhād amṛta-drava-saṁyutam

pibata bhāgavataṁ rasam ālayam

muhur aho rasikā bhuvi bhāvukāḥ

“It is the fruit of the tree of thought (Vedas) mixed with the nectar of the speech of Śukadeva. It is the temple of spiritual love! O! Men of Piety! Drink deep this nectar of Bhāgavata repeatedly till you are taken from this mortal frame.” (SB 1.1.3)

Then the sāragrāhī or the progressive Vaiṣṇava adds:

surasa-sāra-yutaṁ phalam atra yat virasat adi-viruddha-guṇam ca tat

tyāga-virāgamito madhu-payinaḥ rasika-sāra-rasaṁ piba bhāvukaḥ

“That fruit of the tree of thought is a composition, as a matter of course of the sweet and the opposite principles. O! Men of piety, like the bee taking honey from the flower, drink the sweet principle and reject that which is not so.”

The Bhāgavata is undoubtedly a difficult work and where it does not relate to picturesque description of traditional and poetical life, its literature is stiff and its branches are covered in the garb of an unusual form of Sanskrit poetry. Works on philosophy must necessarily be of this character. Commentaries and notes are therefore required to assist us in our study of the book. The best commentator is Śrīdhara Svāmi and the truest interpreter is our great and noble Caitanya deva. God bless the spirit of our noble guides.

These great souls were not like comets appearing in the firmament for a while and disappearing as soon as their mission is over. They are like so many suns shining all along to give light and heat to the succeeding generations. Long time yet they will be succeeded by others of their mind, beauty and caliber. The texts of Vyāsa are still ringing in the ears of all theists as if some great spirit is singing them from a distance! Badarikāśrama! The seat of Vyāsa and the selected religion of thought! What a powerful name ! The pilgrim tells us that the land is cold! How mightily did the genius of Vyāsa generate the heat of philosophy in such cold region! Not only did he heat the locality but sent its ray far to the shores of the sea! Like the great Napoleon in the political world, he knocked down empires and kingdoms of old and bygone philosophy the mighty stroke of his transcendental thoughts! This is real power! Atheist, philosophy of Śaṅkha, Cāravaka, the Jains and the Buddhists shuddered with fear at the approach of the spiritual sentiments and creations of the Bhāgavata philosopher! The army of atheists was composed of gross and impotent creatures like the legions that stood under the banner of the fallen Lucifer; but the pure, holy and spiritual soldiers of Vyāsa, sent by his Almighty Father were invincibly fierce to the enemy and destructive of the unholy and the unfounded. He that works in the light of God, sees the minutest things in creation, he that works the power of God is invincible and great, and he that works with God’s Holiness in his heart, finds no difficulty against unholy things and thoughts. God works through his agents and these agents are styled by Vyāsa himself as the Incarnation of the power of God. All great souls were incarnations of this class and we have the authority of this fact in theBhāgavata itself:

avatāra hy asaṅkhyeya hareḥ sattva-nidher dvijaḥ

yathavidasinaḥ kulyaḥ sarasaḥ syuḥ sahasrasaḥ

“O Brahmins! God is the soul of the principle of goodness! The incarnations of that principle are innumerable! As thousands of watercourses come out of one inexhaustible fountain of water, so these incarnations are but emanations of that infinitely good energy of God which is full at all times.”

The Bhāgavata, therefore, allows us to call Vyāsa and Nārada, as śaktyāveśavatāras of the infinite energy of God, and the spirit of this text goes far to honour all great reformers and teachers who lived and will live in other countries. The Vaiṣṇava is ready to honour all great men without distinction of caste, because they are filled with the energy of God. See how universal is the religion of Bhāgavata. It is not intended for a certain class of the Hindus alone but it is a gift to man at large in whatever country he is born and whatever society is bred. In short Vaiṣṇavaism is the Absolute Love binding all men together into the infinities unconditioned and absolute God. May it, peace reign for ever in the whole universe in the continual development of its purity by the exertion of the future heroes, who will be blessed according to the promise of the Bhāgavata with powers from the Almighty Father, the Creator, Preserver, and the Annihilator of all things in Heaven and Earth.